Coprolite: Mining for Poo in Cambridge

Tom Harvey-James from Groundsure looks at one of the more curious and lesser known resources mined from the ground in a part of East Anglia that you would least expect. Thanks to our dinosaur ancestors, they have found a vital answer to a major 19th Century food issue, whose mining legacy is still picked up on the edge of one of our most celebrated and historic cities.

1815 marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars, a 23-year barrage of conflict concluded by the Duke of Wellington’s crushing defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte’s army at the Battle of Waterloo. These wars led to an unexpected surge in an industry yet to have been truly harnessed. The conflict had led to a shortage of crops and food, in turn creating a growing demand for fertiliser. A rich new source of this was unexpectedly discovered by labourers in the brick fields between Victoria and Chesterton Road in Cambridge as per the map below. Coprolite was discovered but it took a while to understand what it ACTUALLY was.

19th century and present day mapping showing bricks works and development around the former site

What is Coprolite?

Coprolite is the fossilised faeces of dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Roaming around approximately 110 million years ago, these creatures saw what is now modern day Cambridge as the perfect place to use as one large toilet. Fast forward to the 19th Century and these vast deposits of fossilised poo were causing a constant problem for local brick workers, who commonly complained that bricks containing coprolite would simply explode in the kilns.

It was soon however realised these prehistoric poos held the answer that the local agricultural industry had been looking for. If the faecal matter was ground down into a fine powder and water introduced, what you were left with was an extremely nutrient rich fertiliser.

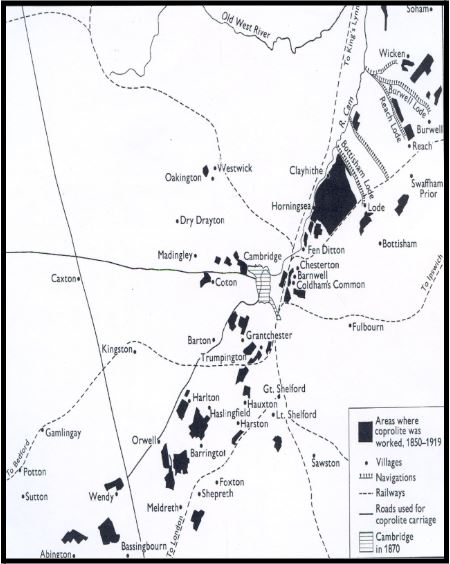

The plan below shows the vast areas exploited for coprolite in and around Cambridge, including Coldham’s Common, one of the first places mined for coprolite in the area. Between 1850 and 1890, Cambridgeshire was producing the vast majority of raw phosphate for fertiliser in Britain, equating to around 54,000 tons and with a commercial value back then of approximately £150,000 per year. To compare that to a modern day equivalent, the National Archives suggests that in 2017, that would equate to the value of approximately £17million.

Source: CSS Vol 13 part 5 pp.11

Extensive evidence of dig sites

The workings typically involved quarrying or digging linear pits to remove the overlying geology, exposing the coprolite deposits below. These would then be extracted by hand using picks and shovels – an extremely labour intensive task.

The industry began to decline as it became cheaper to import fertilisers from overseas. But after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the industry saw somewhat of a revival, due to a shortage of importable and other more localised fertiliser stocks.

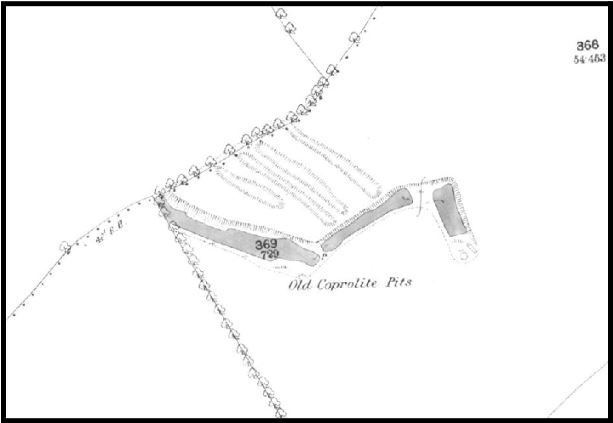

Whilst little remains of the mines today, the historical sources help paint a picture as to the extent of this industry across the region. Evidence of later and typically deeper mining operations can be seen on the Ordnance Survey mapping from 1887 below. However, a lot of the earlier quarries remain scarcely recorded. Evidence is available for some of the initial coprolite diggings, however the accuracy of these sources is somewhat poor. They had a tendency to show larger blanket areas that were mined rather than the extent of the individual pits themselves.

Interpreting the mines

Here is where the mining consultants really add value, by referring to a collective suite of sources, both historical and modern, we can interpret and provide a professional view as to what areas are likely to be affected by historic coprolite mining operations. Using the datasets in tandem with one another, maps from the 1800s, paper geological plans benefitting from hand annotated field notes and harnessing the powers of modern LiDar and InSAR satellite data applications we can provide an holistic and professional assessment of the historical mining risk for your clients.

We know from our own research that the deposits of coprolite were reportedly rarely deeper than 3 feet thick. Whilst the excavations themselves could extend to a depth of 20 feet in some cases, it was more common for the miners to dig a series of shallow linear trenches parallel to one another.

This meant that when one trench was spent, the spoil from the neighbouring trench could be used as backfill, even down to replacing the topsoil. It was crucial in this period, where there was huge agricultural demand, that the land be returned to something capable of cultivation as soon as possible.

In the majority of cases, shallow trenches were dug and soon after infilled using an “as-dug” material. Knowing this allows us to address the risk better by having this deeper understanding of the workings. In many cases, in certain areas around Cambridge, we can provide a property with a passed result, meaning no further action would be recommended.

That said, in some cases we are aware that pits were dug much deeper as the deposits were richer. These pits were often left open and re-explored on several occasions, some even appearing on the first edition Ordnance Survey mapping of the area. These deeper workings that remained operational long after the aforementioned trenches had been backfilled, pose a unique and separate kind of risk. Not knowing the nature of any remediation for these more extensive features, along with the fact that their scale was much larger, we would assess the risk in a different way.

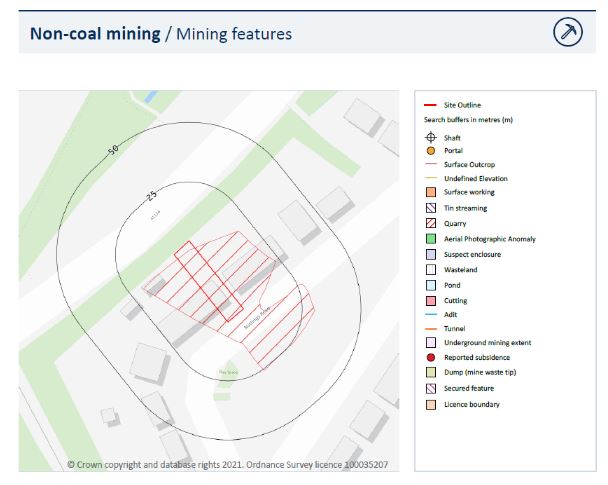

Below is a map extract from a Groundsure Avista report. This shows the property in relation to any recorded non-coal mining features. In this case, the property lies within an area our consultants have identified as being worked to extract coprolite.

These workings are visible on early OS mapping and their extent is shown in detail. This leads us to believe they are depicting the later, deeper style of workings mentioned above and not the shallow linear trenching.

Here, we would recommend some further action to the homeowner in the form of a visual inspection by a qualified surveyor as a way of addressing this potential settlement risk.

Understanding the range and impact of mining types on transactions

While its origins are quirky, coprolite is one of dozens of different types of minerals and resources extracted in an often informal, poorly recorded way. From our nationwide mining archive combined with records from trusted providers including The Coal Authority and British Geological Survey, we have developed exclusive research which shows how mining for minerals other than well known coal mines is far wider and more extensive close to and in some of our major cities.

Mining data of all types, including coal, tin, limestone and indeed dinosaur poo is included automatically in our Avista report. It provides the most comprehensive view of past and present mining risks of all existing types and provided alongside our ClimateIndex forward climate analysis, contaminated land risk and flood risk assessments, to provide your clients with the maximum due diligence and meet compliance with all Law Society and UK Finance handbook guidance. Where issues are found, our expert consultants are on hand to guide you to a positive outcome.

For more information on the mining services and support, together with Groundsure’s Avista report, contact PALI Ltd on 0800 023 5030 or email us at sales@paliltd.com

Tom Harvey-James, Groundsure.